Combination Product Industry News & Guidance

Sharing device-related information and wisdom

that will help you succeed

Seven Common Misconceptions About Implementing A Combination Product Quality Management System

While a Combination Product is made up of a drug constituent and a device constituent, your quality management system needs to be more than simply a combination of drug GMPs (Good Manufacturing Practices) and device GMPs. Whether you are new to the combination product game or working within a new combination product technology space, below you will find a list of common misconceptions or challenges that both drug and device companies face when entering each other’s worlds.

1. COMBINATION PRODUCT = DRUG + DEVICE + HOW THEY INTERACT TOGETHER

A common element missed in the regulatory strategy of a combination product is the interaction of drug and device. A common misconception is that you can marry usual regulatory requirements for drugs with usual regulatory requirements for devices and wind up with an approved coupling of two constituents. However, a happy marriage in the combination product world (and perhaps in life) requires the consideration of how the drug and device get along with each other. This pertains to their physical/chemical compatibility, their joint human factors useability for particular populations, etc. And, even if they would be approved individually, without proving compatibility between drug and device, your regulatory body will not approve the marriage (aka. combination product).

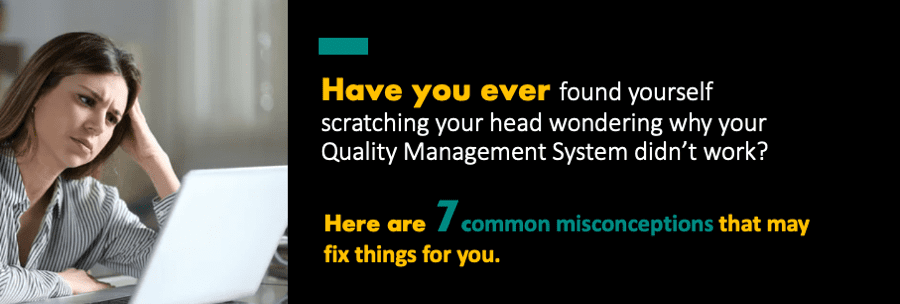

2. DRUG AND DEVICE QUALITY PROCESSES ARE FUNDAMENTALLY DIFFERENT.

While there are similarities between drug and device GMPs, there are also key differences that are often overlooked.

The main reason for this is that the development processes are fundamentally different. Drugs are “discovered” for the most part (some genetics can be designed but with a similar drug process). From a quality perspective, the specs and what is known about the drug product from a CMC perspective is discovered as you go along. For a device, however, it is not a matter of discovery but of setting design controls. You define your characteristics up front, design or select a product that fits these pre-determined criteria, then test and validate that it works as expected.

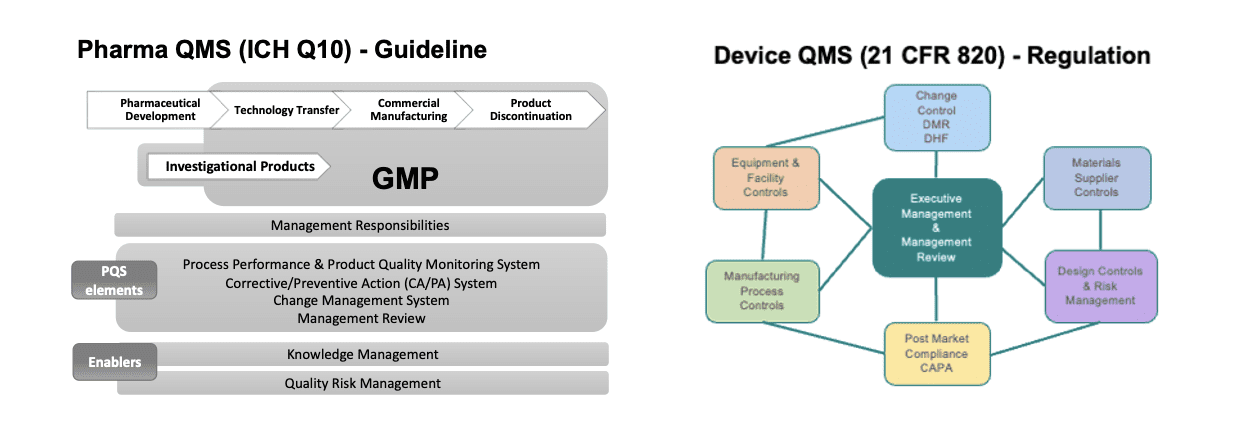

The Drug Discovery Process

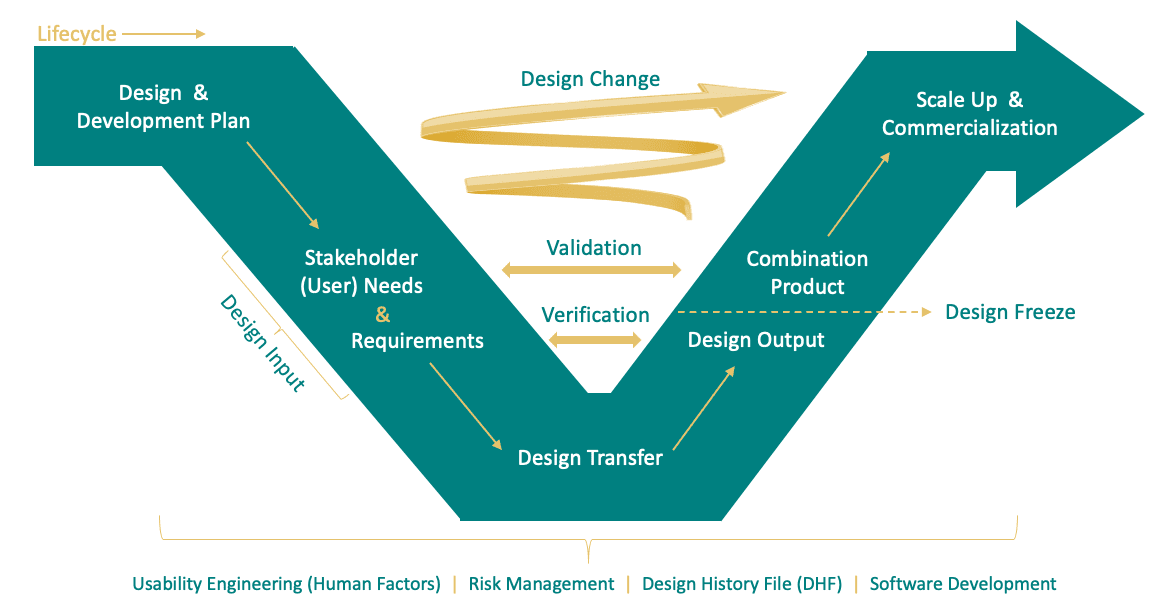

The Combination Product Development Model (derived from the INCOISE model)

When working on a combination product, process and QMS differences come up daily, and it can be difficult to square one to the other. How do you get “typically drug” and “typically device” teams to work together? Combination product development must integrate with drug clinical development and go beyond purely “having a product available” at a given point in time. They need to understand both processes, how they fit together, and the circumstances in which the teams need to work together. Clinical development team members should contribute to device product development. The cross-functional combination product team should discuss options available and determine the most suitable pathway. Device functions should engage their respective counterparts (e.g. development, quality, regulatory) to inform them about differences in the development processes, risk management, resources needed, documentation, and regulatory submissions.

3. A DEVICE QUALITY MANAGEMENT SYSTEM IS REQUIRED FOR COMBINATION PRODUCTS…EVEN DURING CLINICAL DEVELOPMENT

Drug GMPs are followed on a phase-appropriate basis as a drug goes into clinical trials of phases 1-3. However, what many combination product developers neglect is that design controls for the device constituent need to be considered from the start of clinical development. In our client work, we find that many drug companies new to the combination product arena are commonly not aware of this need until remediation is necessary and that many find it difficult to know how to apply device GMPs efficiently within their drug’s clinical development process. The “how” is generally dependent on many factors, including, but not limited to, the type of combination product under development, the implementation and depth of current drug QMS, suppliers and contract manufacturers involved and their respective QMSs, and personnel and resources available within the company.

The success rate of drugs at various phases varies drastically. 90% won’t make it to approval…when do you start device development so you start early enough and not waste resources on a drug that won’t work in the end? That answer will be a little different for each company, and each drug delivery device system project.

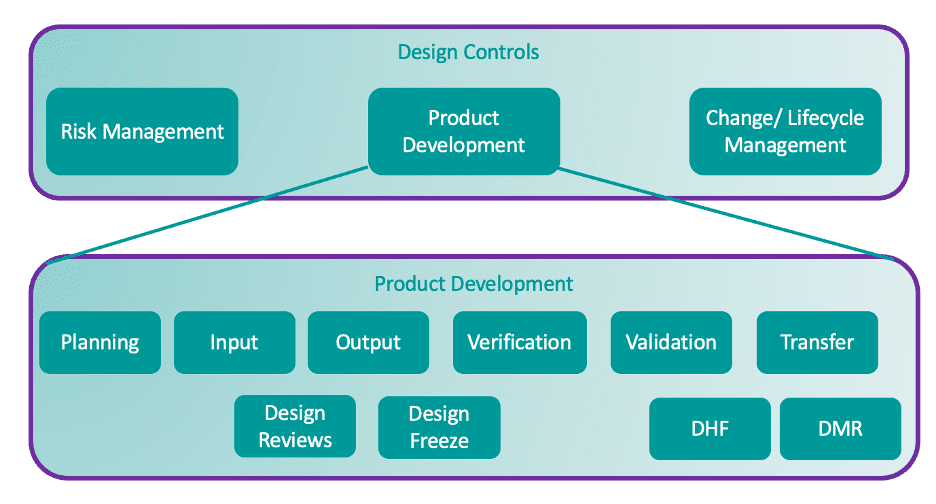

4. DESIGN CONTROLS ARE A QMS REGULATORY REQUIREMENT

Many don’t realize that they are moving from QMS situation based on guidelines to one based on requirements. While ICH Q8 is a guideline for drug design controls, 820.30 is a regulatory requirement for devices and combination products. Development for these products is a GMP activity, even though it is not for pharmaceutical development. That said, while design controls for the drug and device constituents have different regulations, standards, scope, and outputs, there are similarities in design control activities that can assist the alignment of processes.

5. IT’S NOT A CHECKLIST, BUT A PROCESS

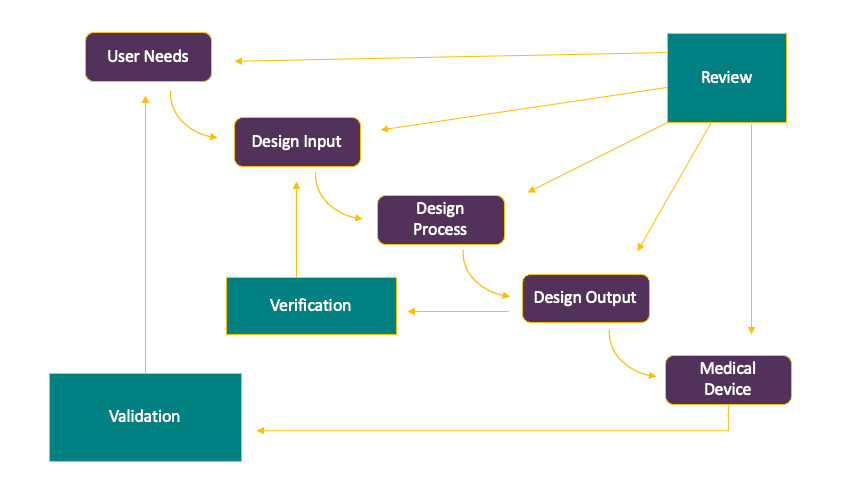

Often, drug companies don’t realize that design control for a combination product isn’t a series of activities that need to be performed and checked off your list, but an iterative process based on review, validation, and verification activities that inform the ultimate design of the combination product.

Add to that the fact that drug development decisions will affect device development decisions, and you come to the conclusion that not only is it important to coordinate communication and collaboration across departments in combination product development, but a strong understanding of both drug and device development is required to determine the best method of inserting a combination product development process within your existing drug development process.

6. DRUG AND DEVICE TEAMS DO NOT SPEAK THE SAME LANGUAGE

Often, drug and device developers don’t take the time to learn each other’s language. Combination product development marries the work of two very different worlds, and as a manufacturer in France speaks one language and his counterpart in Spain speaks another, so is the case for drug developers and device developers. They not only have a different vernacular for similar, or sometimes the same, things, but their approaches to tackling certain complimentary activities are also usually unique to their own drug or device culture and best practices. Aligning their processes can begin with translating terminology to find functional similarities.

Drug Development (QbD) Device Development (Design Controls)

Master Project Plan……………………………………………….Design & Development Plan

Quality Target Product Profile…………………………..…..User Needs & Design Inputs

CQA, Control Strategy………………………………………..….Design Outputs

CMC Stage Gate Reviews…………………………………..…..Design Reviews

Characterization / Stability………………………………..…..Design Verification

Clinical Studies………………………………………………..……..Design Validation

Guidance on Medication Errors………………………..……Human Factors

Technology Transfer………………………………………..……..Design Transfer

Product Dossier & Dev. Reports………………………..……Design History File

Master Batch Record………………………………………..…….Device Master Record

Risk Management ICH Q9………………………………..……..Risk Management ISO 14971

Change Control……………………………………………………….Design Change Control

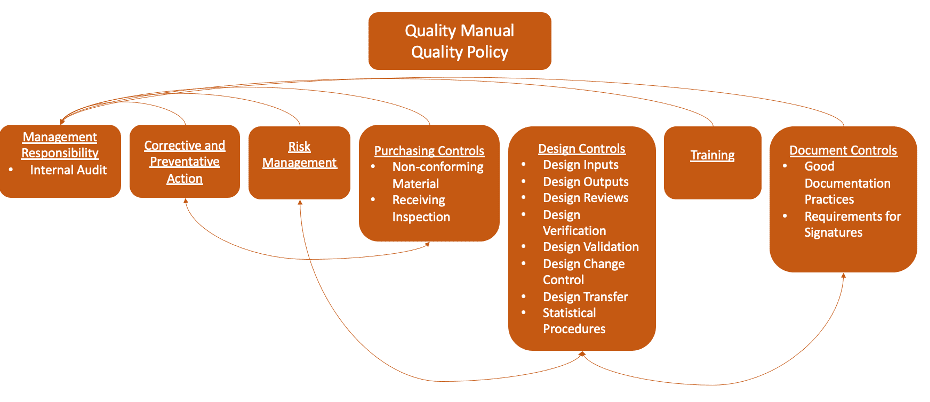

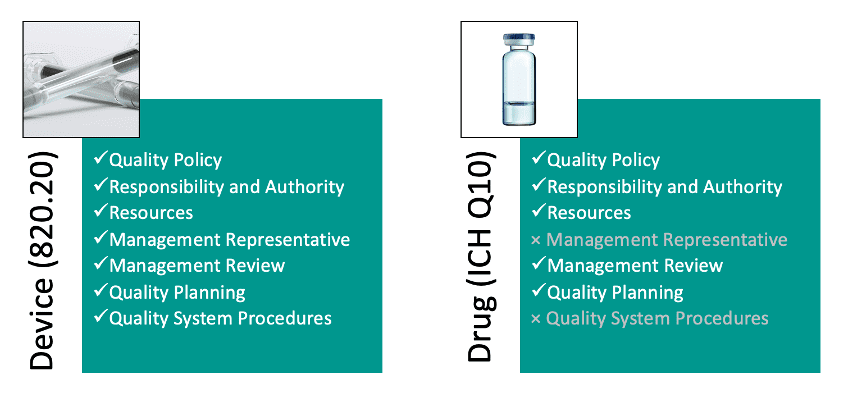

7. MANAGEMENT RESPONSIBILITY TASK LIST LOOKS IDENTICAL, BUT SCOPE DIFFERS

A lot of management responsibility obligations with regard to ensuring a compliant QMS in combination products are already done for drugs, but many don’t understand that they usually need to be done differently or to a different extent for when applied to combination products. It is important to assess the differences and educate management on how their job might change when Quality Policy or Management Review (for example) are applied to devices vs what they are used to in the drug sphere.

AUTHOR

Jonathan Amaya-Hodges, Director, Technical Services, Suttons Creek, Inc. – Jonathan has over 16 years of multidisciplinary experience in regulated medical products (drugs, biologics, medical devices, and combination products) at multiple global companies. He has practical experience in Development/Engineering, Quality Assurance, and Regulatory Affairs for various types of combination products with a focus on drug delivery. Additional background includes digital health (including smart packaging/connected devices and software as a medical device, or SaMD) and in vitro diagnostics, along with clinical development (bridging) and lifecycle management for combination products. Jonathan engages with the global combination product community by speaking at conferences, lecturing in courses, serving key roles within prominent industry organizations, and interfacing with regulators on a variety of topics.